Mohsen Mosleh, Gordon Pennycook, David G. Rand

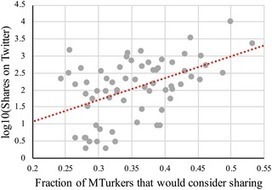

There is an increasing imperative for psychologists and other behavioral scientists to understand how people behave on social media. However, it is often very difficult to execute experimental research on actual social media platforms, or to link survey responses to online behavior in order to perform correlational analyses. Thus, there is a natural desire to use self-reported behavioral intentions in standard survey studies to gain insight into online behavior. But are such hypothetical responses hopelessly disconnected from actual sharing decisions? Or are online survey samples via sources such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) so different from the average social media user that the survey responses of one group give little insight into the on-platform behavior of the other? Here we investigate these issues by examining 67 pieces of political news content. We evaluate whether there is a meaningful relationship between (i) the level of sharing (tweets and retweets) of a given piece of content on Twitter, and (ii) the extent to which individuals (total N = 993) in online surveys on MTurk reported being willing to share that same piece of content. We found that the same news headlines that were more likely to be hypothetically shared on MTurk were also shared more frequently by Twitter users, r = .44. For example, across the observed range of MTurk sharing fractions, a 20 percentage point increase in the fraction of MTurk participants who reported being willing to share a news headline on social media was associated with 10x as many actual shares on Twitter. We also found that the correlation between sharing and various features of the headline was similar using both MTurk and Twitter data. These findings suggest that self-reported sharing intentions collected in online surveys are likely to provide some meaningful insight into what content would actually be shared on social media.

|

|

Suggested by mohsen mosleh |

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...